What nutrients are required for the proper functioning of the entire epidermis layer of the skin?

What nutrients are required for the proper functioning of the entire epidermis layer of the skin?

Are they the same as the nutrients needed for the whole body? Does the cell require all the macro-nutrients as fats, proteins and carbohydrates?

Does the cell require all the micro-nutrients such as the minerals and vitamins and water? The challenge is that the epidermis has no blood supply and therefore must rely on nutrients coming from the vascular system in the dermis. [1]

Inside the epidermis there is a veritable factory of vast proportions, even though the epidermis is only as thick as a tissue; ranging from 62.62 micrometres on the upper lip to the thinnest at posterior auricular area being 29.57 micrometres [1] Whereas the cell membrane is only 1 cell thick and that too is an incredible factory allowing the manufacture and collecting of substances and packing them up and sending them off to where they need to go.

There are four main cells within the epidermis: The keratinocyte, the melanocyte, the Merkel cell and one that comes and goes, is the Langerhans cell. The cell membranes are vital to the viability of these cells. The membranes surrounding the cells and surrounding the organelles are subjected to oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. The melanocyte is more susceptible to these factors because melanogenesis is an oxidative process in itself and needs more antioxidants than the others. There are approximately 80% of keratinocytes to 7% melanocytes,8% of Merkel cells and 5% of Langerhans cells.

The membranes are reliant upon the food that is consumed by that person to ensure that both the cell membrane and the organelles are viable. The nutrients are then reliant upon many factors; the age of the person; which then has a bearing upon the microbiome as well as the lifestyle and diet of the person.

The keratinocytes are forever changing; differentiating from the moment it is seen as a stem cell to a transit amplifying cell to when it finally let’s go as a corneocytes of its desmosomal filaments and disengages and falls off. The corneocyte is a protein enriched cell which is living in a lipid-rich matrix environment of many ceramide species, free fatty acids and cholesterol which forms the stratum corneum.

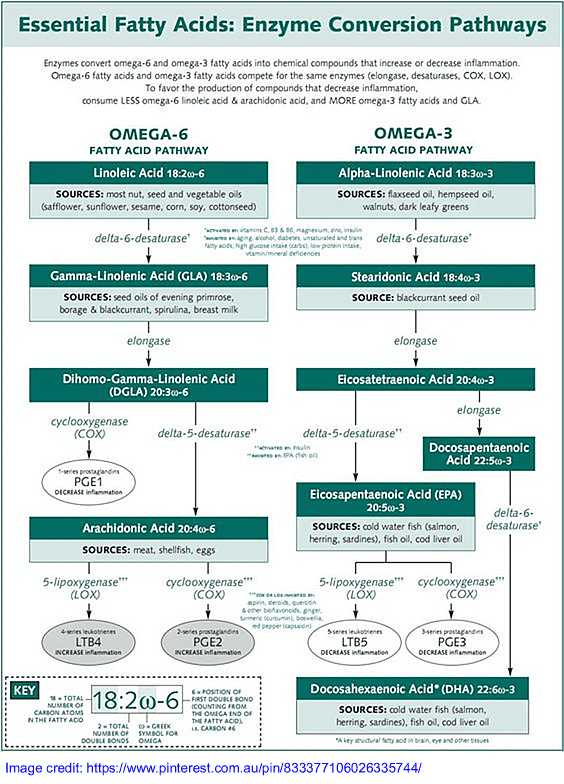

The eicosanoid, endocannabinoid,N-acyl ethanolamide, and sphingolipid families are important in the skin. A number of cyclooxygenase (COX)-derived prostaglandins (PG), hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETE), hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODE), and the lipoxygenase (LOX)–derived leukotrienes (LT) have been identified in human skin and contribute to keratinocyte proliferation, melanocyte dendricity, photocarcinogenesis, allergy, and inflammation. [14]

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (n-3 PUFA) are termed essential fatty acids because they cannot be synthesized by humans due to the lack of delta-12 and delta-15 desaturase enzymes. The keratinocytes have a low desaturase activity which results in not being able to form long chain poly unsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) sufficiently and therefore the essential fatty acid of linoleic acid must come from either the diet or through supplementation. Linoleic acid forms ceramides which are part of the barrier defences of the epidermis [2] A low delta-6 desaturase has been linked to many skin abnormalities. Desaturase alter the lipid composition of the skin, thereby affecting skin barrier homeostasis and consequently, whole body energy balance [3]

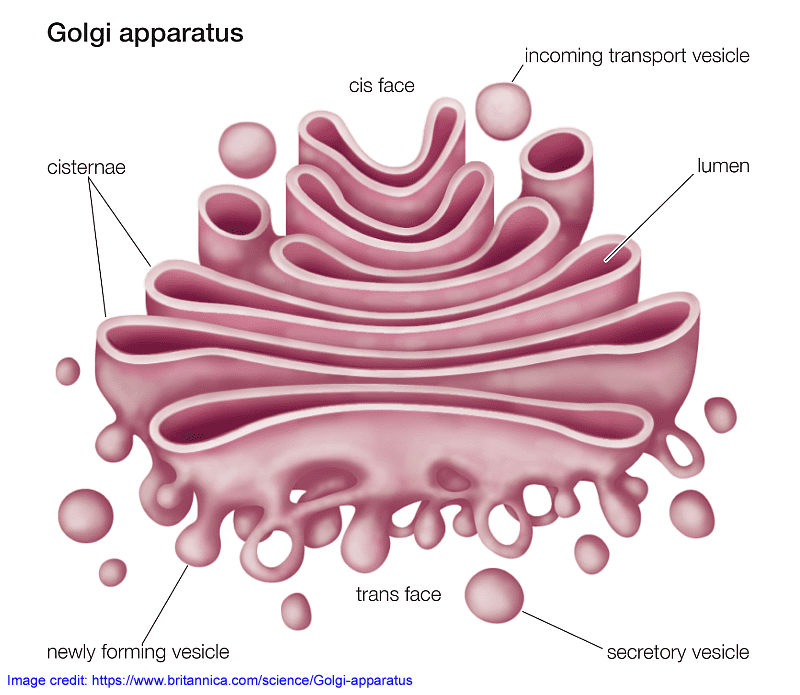

The corneocytes are bathed in a sea of a multi-lamellar lipid structure of 1:1:1 of ceramides, cholesterol and nonessential fatty acids. This mixture is a significant part of the barrier function of the stratum corneum. [4] There is some evidence to support that lamellar granules that are bounded by a membrane originally came from the trans-golgi apparatus. The lipid content includes phosphoglycerides, glucosylceramides and sphingomyelin. They also contain proteases and antimicrobial peptides. If these are lamellar granules are defective, then the barrier function is also defective. [5]

The Golgi apparatus or body is responsible for transporting, modifying, and packaging proteins and lipids into vesicles for delivery to targeted destinations. It is located in the cytoplasm next to the endoplasmic reticulum and near the cell nucleus. ), The “trans” (cisternae farthest from the endoplasmic reticulum) faces, are responsible for the essential task of sorting proteins and lipids that are received (at the cis face) or released (at the trans face) by the organelle. [6]

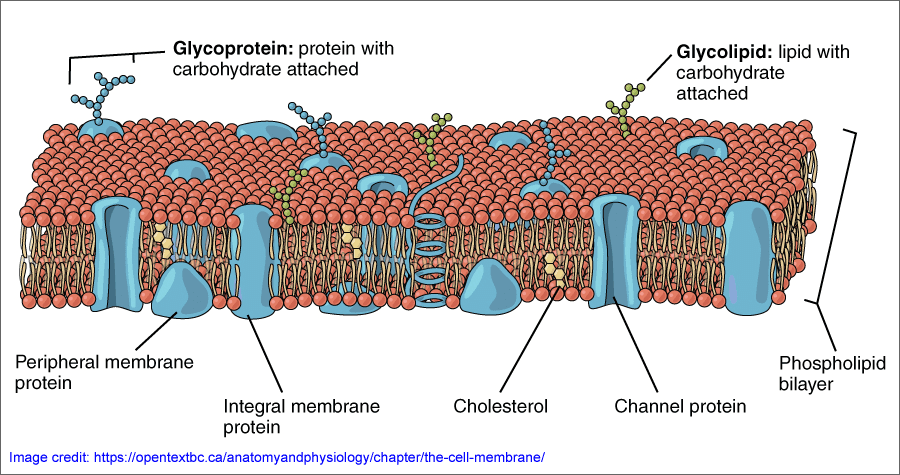

The membranes of both the cells and their organelles are made up of phospholipids, cholesterol and proteins. Various substances have the ability of going through the cell membrane, for example glucose uses facilitated diffusion through a specialized carrier protein called the glucose transporter to transfer the glucose. Amino acids also use a type of facilitated diffusion to go through the cell membrane [7]

Vitamin C is transported across the cell membrane via specific sodium dependant vitamin C transporters (SVCT1 and SVCT2). Both transporters are hydrophobic membrane proteins that co-transport sodium, which drives the uptake of vitamin C into the keratinocyte. [1]

Dietary lipids

Dietary lipids are a vital component so that the cell /plasma membrane can function at optimum capacity. If the diet is one of low to no lipids, then the skin as a whole is compromised and can be dry and flaky. The ceramides allow a barrier to be present to stop fast trans epidermal water loss.

The long-chain omega-esterified ceramides found in the stratum corneum are considered structural lipids pivotal for the integrity of the epidermal barrier, and recent studies have revealed their diversity of structure and physiological functions.

In contrast, non-hydroxylated ceramides and sphingoid bases are important mediators of immune cell regulation, with roles in homeostasis and inflammation. [14]

Ceramides can be found in foods: brown rice, wheat (although they have their problems). Sphingolipids, which contain ceramides, are present in in dairy products, eggs, salmon, avocado and soybeans.

Blocking factors for ceramides:

Cholesterol-lowering drugs alter ceramide and lipid levels in the upper levels of the epidermis.

Omega 3

Omega 3 includes α-linolenic acid (ALA) eicosapentaenoic (EPA) docosahexaenoic (DHA) and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA). Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) is a long-chain, highly unsaturated omega-3 (n-3) fatty acid. It has a structure that gives it unique physical and functional properties. [13] DHA is metabolically related to other n-3 fatty acids: it can be synthesised from the plant essential fatty acid α-linolenic acid (ALA). However, this pathway does not appear to be very efficient in many individuals, although the conversion of ALA to DHA is much better in young women than in young men. [12]

Both EPA and DHA are long-chain fatty acids, while ALA is a short-chain fatty acid:

Both EPA and DHA break down slowly in the body and are found in marine sources. They produce eicosanoids which are anti-inflammatory.

The short chain ALA is rapidly absorbed into the body and are found in plants and some dairy, eggs and some fish. They are neutral in pro and anti-inflammatory reactions. In the original paleo diet the ratio, we are led to believe, was 1:1 omega 6 to 3. Therefore, we had both pro-inflammatory sources and anti-inflammatory sources for wound healing functions. Now, according to many sources, the western diet can be as much as 50 to 1.

The protein estimated average requirement (EAR) for dietary protein is 0.66 g/kg/day and the Food and Nutrition Board recommends a recommended dietary allowance RDA of 0.8 g/kg/day for all adults over 18 years of age, including elderly adults over the age of 65. [9]

Animal protein is recognised by scientists as superior it has a complete composition of essential amino acids, with high digestibility and bioavailability. Plant proteins are often described as incomplete, due to the insufficient amounts of all nine essential amino acids. Protein found in legumes are limited in methionine and cysteine; cereals (lysine, tryptophan); vegetables, nuts and seeds (methionine, cysteine, lysine, threonine); seaweed (histidine, lysine). In addition, the digestibility and bioavailability of plant proteins is lower than those from animal sources, due to the high content of dietary fibre and plant bio-compounds.

Apart from protein, animal-based foods provide heme-iron, cholecalciferol, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), vitamin B12, creatine, taurine, carnosine and conjugated linoleic acid all compounds not present in plant-based foods. On the other hand, foods of animal origin contain saturated fatty acids. There is a large body of evidence that processed meat is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, dyslipidaemia and some forms of cancers and is classified as group 1 carcinogen.

Phytochemicals from plant proteins are being now increasingly associated with beneficial effects, e.g., regulating blood glucose level, improving lipid profile and reducing the risk of certain cancers. [11]

Glucose is the primary source of energy in keratinocytes and provides the carbohydrate backbone for glycosylation of proteins/lipids that comprise the extracellular environment of the skin, suggesting that altered levels of glucose in skin may cause structural changes and abnormal barrier functions; as in seen in the skin condition of glycation. High glucose has also been shown to inhibit proliferation in epidermal keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. While high levels of glucose significantly enhance calcium-induced keratinocyte differentiation, their proliferation is inhibited. Because a well-balanced proliferation and differentiation process is one of the critical steps in wound healing, high glucose levels might contribute to impaired wound healing in certain diseases, including diabetes. [17]

In total, humans require 13 vitamins: four fat soluble vitamins (A, D, E, K) and nine water soluble vitamins, which comprise vitamin C and the eight B vitamins: thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid (B5), vitamin B6, folate (B9) and vitamin B12. [10] The modern Western diet of processed foods is associated with decreasing vitamin and mineral intake.

Vitamin A

Vitamin A is a fat-soluble vitamin and also comprises of a group of unsaturated nutritional organic compounds. These compounds include preformed vitamin A that exist in the form of retinol (alcohol), retinal (aldehyde), retinoic acid (irreversibly oxidized form of retinol) and several pro-vitamin A carotenoids (mainly β–carotene).

Retinol is a yellow fat-soluble substance, an absorbable form of vitamin A present in animal food sources. This chemical structure makes it poorly soluble in water but easily transferable through membrane lipid bilayers. Vitamin A and its derivatives, play an important role in regulating proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis in skin cells. Keratinocytes and fibroblasts express both retinoid receptors skin is considered as one of the major retinoid-responsive tissues. [17]

The bioavailability of carotenoids in food is variable because the efficacy of metabolic processes that convert carotene into retinol varies from one person to another.

The preformed vitamin A can only be obtained from the diet in food of animal origin and is the most abundant form of vitamin A in the human body.

Foods rich in retinol include meat, butter, retinol-enriched margarine, dairy products and eggs, while foods rich in β-carotene include vegetables and fruits (e.g. sweet potatoes, carrots, dark-green leafy vegetables, sweet red peppers, mangoes, melons). [17]

B vitamins

B vitamins act as coenzymes in enzymatic processes that underpin every aspect of cellular physiological functioning. At least one or more of B vitamins such as thiamine, niacin, pantothenic acid and riboflavin are associated with the essential process of generating energy (ATP) and coenzymes in both cellular energy production and aerobic respiration in the mitochondria [10]

Dermatological signs of B vitamin deficiency include a patchy red rash, seborrhoeic dermatitis, fungal skin and nail infections (1) Vitamin B can be found in many foods such as pork, as well as legumes, seeds and nuts. B12 can be found in dairy particularly Swiss cheese and yogurt as well as trout and wild salmon.

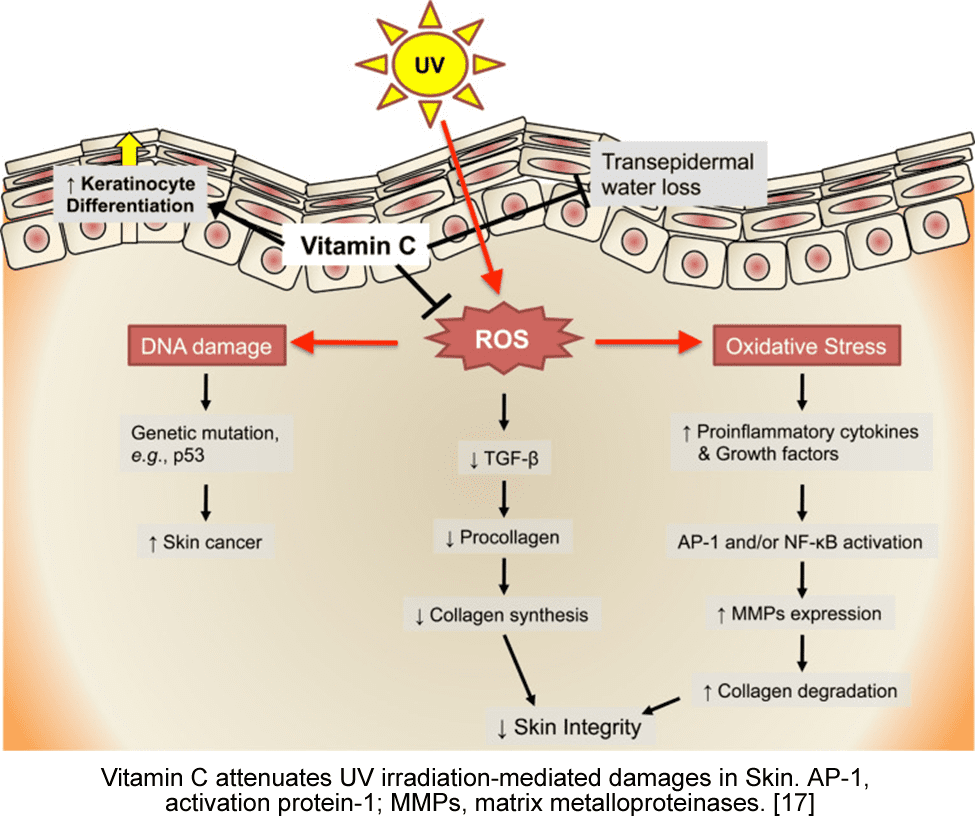

Ascorbic acid

The hydroxylation reaction requires both oxygen and the reducing agent; ascorbic acid (this is the active form of vitamin C). This is needed as a co enzyme for the hydroxylation of both prolyl and lysyl residues of collagen. Without the ascorbic acid, collagen fibres cannot cross link and then the person will be subjected to scurvy. Vitamin C is also partly responsible for the differentiation of the keratinocyte. It also suppresses UV irradiation-triggered production of free radicals, protecting cells from oxidative stress [17]

Vitamin C significantly increases epidermal moisture content, improving skin hydration (17)

The epidermis contains between 6-64 mg/100g vitamin C and the dermis contains between 3-13 mg/100g vitamin C which is well above plasma concentrations. It is mainly in intracellular compartments and is transported into the cells from blood in the dermis. It has been reported that vitamin C levels are lower in photodamaged and aged skins. Pollutants and ultraviolet radiation are some of the culprits associated with oxidative stress. (1) Urocanic acid, which is generated from histidine in skin, is a potent, endogenous UV absorbent. (17) The major source of histidine is filaggrin.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C is required for the absorption and metabolism of iron in the human body. The transfer of iron to the cells of the skin probably occurs from the plasma pool. Iron is re‐absorbed into the plasma from epidermal cells as they mature. Transferrin‐bound iron is absorbed into epidermal cells by a process of receptor‐mediated endocytosis at cell membranes, the iron being released subsequently for incorporation in ribonucleotide reductase and other enzymes in the cell cycle. The iron content of the skin varies according to the age, sex, race and state of health of an individual, and from one part of the body to another, reflecting the skin, hair and nail colour and growth patterns. Iron is lost daily in apocrine sweat. Severe iron deficiency is recognized by eczema in the corners of the mouth, skin irritation, and ‘skin itch’ (pruritis). Loss of skin ‘tone’, reduced resistance to infections, and impaired wound healing are also associated with iron deficiency. [15]

Blocking factors: Iron absorption is inhibited by both coffee and tea Drinking coffee and other caffeinated beverages with a meal is associated with a 39–90% reduction in iron absorption. [16]

High levels of vitamin C can be found in both gold and green kiwi fruit, raw broccoli, raw capsicum, citrus, green leafy vegetables as well as pineapple and papaya to name a few. Heat and light diminish the content of vitamin C within the food.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D is synthesized from 7-dehydrocholesterol by two key enzymes, 25-hydroxylase (CYP27A1) and 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 1-α-hydroxylase (CYP27B1), in human skin following UVB irradiation. [17] Wild deep-sea fish and pasture fed chicken’s eggs as well as wild mushrooms which have D2 being a vegetable rather than D3 from animals.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin that is found in the cell membrane and is an antioxidant.

There are a few varieties of vitamin E: α-, β-, γ-, and σ-tocopherols and their related corresponding tocotrienols. γ-tocopherol is the most abundant tocopherol in diet, whereas α-tocopherol is the most abundant vitamin E derivative in human tissues.

γ-Tocopherol levels exceeding those of α-Toc in human skin inhibits the production of PGE2 and nitric oxide, and also prevents sunburn cell formation, ultraviolet (UV) B-induced lipid peroxidation and oedema, therefore it has a role in epidermal protection from oxidative stress. [18]

Unfortunately, Vitamin E is highly sensitive to even a single dose of ultraviolet radiation and may be helped by the addition of vitamin C in the diet. It suppresses lipid peroxidation and modulates photoaging. [17]

Vitamin E is synthesized by plants and must be obtained through dietary sources. They Exhibit anti-inflammatory roles, protection from oxidative stress. Vitamin E also has a role in photo-adduct formation and immunosuppression. [18]

| Some Food Sources of Vitamin E | ||||

| Food | Serving | α-Tocopherol (mg) | γ-Tocopherol (mg) | |

| Sunflower oil | 1 tablespoon | 5.6 | 0.6 | |

| Safflower oil | 1 tablespoon | 4.6 | 0 | |

| Grapeseed oil | 1 tablespoon | 3.9 | 0 | |

| Corn oil | 1 tablespoon | 1.9 | 0 | |

| Olive oil | 1 tablespoon | 1.9 | 0.1 | |

| Soybean oil | 1 tablespoon | 1.1 | 8.7 | |

| Sunflower seed kernels, dry roasted | 1 ounce (28g) | 7.4 | 0 | |

| Almonds | 1 ounce (28g) | 7.3 | 0.2 | |

| Hazelnuts | 1 ounce (28g) | 4.3 | 0 | |

| Peanuts | 1 ounce (28g) | 2.4 | 2.4 | |

| Pecans | 1 ounce (28g) | 0.4 | 6.9 | |

| Peanut butter, smooth | 2 tablespoons | 3.2 | 0 | |

| Tomato sauce, canned | 1 cup | 3.5 | 0.2 | |

| Cranberry juice | 1 cup (8 fl oz/236ml) | 3.0 | 0 | |

| Apricots, dried | ½ cup (halves) | 2.8 | 0 | |

| Avocado | 1 fruit | 2.7 | 0.4 | |

| Fish, rainbow trout, cooked, dry-heat | 3 ounces (85g) | 2.4 | 0 | |

| Spinach, cooked | ½ cup | 1.9 | 0 | |

| Asparagus, canned | ½ cup | 1.5 | 0 | |

| Swiss chard, cooked | ½ cup (chopped) | 1.6 | 0 | |

| Broccoli, cooked | ½ cup (chopped) | 1.1 | 0 | |

| Blackberries, raw | ½ cup | 0.8 | 0.3 | |

| Reference [20] | ||||

Minerals, including zinc, copper, and selenium, also have an important role in maintaining skin health. Zinc is an essential cofactor of numerous metalloenzymes. Its main function is to protect the skin against photodamage by absorbing UV irradiation, limiting penetration of radiation into skin. Co-treatment with zinc and vitamin C exhibits antimicrobial activity that helps to clear bacteria in acne.

Copper is known to stimulate the maturation of collagen, thus is critical in improving skin elasticity and thickness. While it also plays a role in melanin synthesis enables pigmentation of skin and hair.

Lastly, selenium protects the skin from UV irradiation-induced oxidative stress by stimulating the activities of the selenium-dependent antioxidant enzymes, glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin reductase, that are present in the plasma membrane of epidermal keratinocytes [18]

| Some Food Sources of Copper | ||

| Food | Serving | Copper (μg) |

| Liver (beef), cooked, pan-fried | 1 ounce (28g) | 4,128 |

| Mollusks, oysters, eastern, wild, cooked, moist heat | 6 medium | 2,397 |

| Crab meat, Alaskan king, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 1,005 |

| Crab meat, blue, cooked, moist heat | 3 ounces (85g) | 692 |

| Mollusks, clams, mixed species, cooked, moist heat | 3 ounces (85g) | 585 |

| Cashews nuts, raw | 1 ounce (28g) | 622 |

| Sunflower seed kernels, dry roasted | 1 ounce (28g) | 519 |

| Hazelnuts, dry roasted | 1 ounce (28g) | 496 |

| Almonds | 1 ounce (28g) | 292 |

| Peanut butter, chunk style, without salt | 2 tablespoons | 185 |

| Pecans | 1 ounce (28g) | 0.4 |

| Peanut butter, smooth | 2 tablespoons | 3.2 |

| Lentils, mature seeds, cooked, boiled, without salt | 1 cup | 497 |

| Mushrooms, white, raw | 1 cup (8 fl oz/236ml) | 223 |

| Shredded wheat cereal | 2 biscuits | 167 |

| Chocolate (semisweet) | 1 ounce (28g) | 198 |

| Some Food Sources of Zinc | ||

| Food | Serving | Zinc (mg) |

| Oyster, cooked | 6 medium | 27-50 |

| Beef, chuck, blade roast, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 8.7 |

| Beef, ground, 90% lean meat, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 5.4 |

| Crab meat, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 4.7 |

| Fortified, whole-grain toasted oat cereal | 1 cup (236ml) | 3.8 |

| Turkey, dark meat, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 3.0 |

| Pork, loin, blade roast, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 2.7 |

| Soybeans, dry roasted | 1/2 cup (120ml) | 2.2 |

| Chicken, roasting, dark meat, cooked | 3 ounces (85g) | 1.8 |

| Pine nuts | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.8 |

| Cashews | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.6 |

| Yogurt, plain, low fat | 6 ounces (170g) | 1.5 |

| Sunflower seed kernels | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.5 |

| Pecans | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.3 |

| Brazil nuts | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.2 |

| Chickpeas (garbanzo beans), cooked | 1/2 cup (120ml) | 1.2 |

| Milk | 1 cup (236ml) | 1.1 |

| Cheese, cheddar | 1 ounce (28g) | 1.0 |

| Almonds | 1 ounce (28g) | 0.9 |

| Beans, baked | 1/2 cup (120ml) | 0.9 |

About the Author:

About the Author:

Beverly Greenwood is a foundation member of the I.A.C. and the CEO and founder of the Natural Skincare Clinic and College in Melbourne, Australia.

Beverly brings 50 years of experience as a naturopath, skin treatment therapist, and tutor with specialties in a wide variety of topics.

References:

1. The Roles of Vitamin C in Skin Health

Nutrients. 2017 Aug; 9(8): 866.

Published online 2017 Aug 12. doi: 10.3390/nu9080866

PMCID: PMC5579659

PMID: 28805671

Juliet M. Pullar, Anitra C. Carr, and Margreet C. M. Vissers*

2. A Comprehensive Examination of Topographic Thickness of Skin in the Human Face

Aesthetic Surgery Journalwww.aestheticsurgeryjournal.com

2015, Vol 35(8) 1007–1013

© 2015 The American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, Inc.

Reprints and permission:

DOI: 10.1093/asj/sjv079

Karan Chopra, MD; Daniel Calva, MD; Michael Sosin, MD;

Kashyap Komarraju Tadisina, BS; Abhishake Banda, MD, DMD;

Carla De La Cruz, BA; Muhammad R. Chaudhry, MD;

Teklu Legesse, MD; Cinithia B. Drachenberg, MD;

Paul N. Manson, MD; and Michael R. Christy, MD

3. Lipid functions in skin: Differential effects of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids on cutaneous ceramides, in a human skin organ culture model☆

Alexandra C. Kendall a, Magdalena Kiezel-Tsugunova a, Luke C. Brownbridge a,

John L. Harwood b,⁎, Anna Nicolaoua,⁎

a Laboratory for Lipidomics and Lipid Biology, Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Biology, Medicine and Health, University of Manchester, Manchester Academic

Health Science Centre, Manchester M13 9PL, UK

b School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AX, UK

4. The role of fatty acid desaturases in epidermal metabolism

Dermatoendocrinol. 2011 Apr-Jun; 3(2): 62–64.

Published online 2011 Apr 1. doi: 10.4161/derm.3.2.14832

PMCID: PMC3117003

PMID: 21695013

Harini Sampath1 and James M Ntambi 2

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

5. Structure and Function of the Stratum Corneum Extracellular Matrix

Peter M. Elias1

J Invest Dermatol. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 Mar 5.

Published in final edited form as:

J Invest Dermatol. 2012 Sep; 132(9): 2131–2133.

doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.246

PMCID: PMC3587970

NIHMSID: NIHMS444111

PMID: 22895445

6. Epidermal Lamellar Granules

Skin Pharmacol Physiol 2018;31:262–268

Philip Wertz

Iowa City, IA, USA

Received: March 13, 2018

Accepted after revision: July 2, 2018

Published online: August 15, 2018

DOI: 10.1159/00049175

https://www.researchgate.net › publication › 327047387_Epidermal_Lamell...

7. https://www.britannica.com/science/Golgi-apparatus

8. Lippincott Illustrated Reviews: Biochemistry

By: Denise Ferrier

Publisher: Wolters Kluwer Health

Print ISBN: 9781496344496, 1496344499 eText ISBN: 9781496376466, 1496376463

Edition: 7th Format: EPUB

9. Protein Consumption and the Elderly: What Is the Optimal Level of Intake?

Nutrients 2016, 8(6), 359; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8060359

by Jamie I. Baum 1,*, Il-Young Kim 2 and Robert R. Wolfe 2

10. B Vitamins and the Brain: Mechanisms, Dose and Efficacy—A Review

Nutrients 2016, 8(2), 68; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu8020068

by David O. Kennedy

Brain, Performance and Nutrition Research Centre, Northumbria University, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE1 8ST, UK

11. Protein for Life: Review of Optimal Protein Intake, Sustainable Dietary Sources and the Effect on Appetite in Ageing Adults

Nutrients 2018, 10(3), 360; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10030360

by Marta Lonnie 1, Emma Hooker 1, Jeffrey M. Brunstrom 2, Bernard M. Corfe 3,4, Mark A. Green 5, Anthony W. Watson 6, Elizabeth A. Williams 3, Emma J. Stevenson 6, Simon Penson 7 and Alexandra M. Johnstone 1,*

12. Docosahexaenoic Acid.

Ann Nutr Metab. 2016;69 Suppl 1:7-21. Epub 2016 Nov 15.

Calder PC1.

Faculty of Medicine, University of Southampton, and NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and University of Southampton, Southampton, UK.

13. Enhancing Omega-3 Long-Chain Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Content of Dairy-Derived Foods for Human Consumption

Nutrients 2019, 11(4), 743; https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11040743 - 29 Mar 2019

by Quang V. Nguyen, Bunmi S. Malau-Aduli, John Cavalieri, Peter D. Nichols and Aduli E. O. Malau-Aduli

14. Distribution of Bioactive Lipid Mediators in Human Skin

Alexandra C. Kendall1, Suzanne M. Pilkington2, Karen A. Massey3, Gary Sassano4, Lesley E. Rhodes2 and Anna Nicolaou1

Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2015) 135, 1510–1520; doi:10.1038/jid.2015.41; published online 12 March 2015

15. Iron: a cosmetic constituent but an essential nutrient for healthy skin

International Journal of Cosmetic Science Volume 23, Issue 3

A. B. G. Lansdown

First published: 21 December 2001

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-2494.2001.00082.x

16. Inhibition of food iron absorption by coffee.

Am J Clin Nutr. 1983 Mar;37(3):416-20.

Morck TA, Lynch SR, Cook JD.

17. Vitamin A in Health and Disease

By Mohd Fairulnizal Md Noh, Rathi Devi Nair Gunasegavan and Suraiami Mustar

Submitted: September 15th 2018 Reviewed: January 16th 2019 Published: April 17th 2019 DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.84460

18. Vitamin E in dermatology

Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016 Jul-Aug; 7(4): 311–315.

doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.185494

PMCID: PMC4976416 PMID: 27559512

Mohammad Abid Keen and Iffat Hassan

19. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/health-disease/skin-health/vitamin-C

20. https://lpi.oregonstate.edu/mic/vitamins/vitamin-E#food-sources